1 Abstract¶

HiPS is an IVOA-standard protocol for providing a hierarchical, pre-rendered view of sky survey data. It is one of the ways in which Rubin Observatory will make available its survey data to data rights holders. This tech note describes the implementation strategy for the Rubin Science Platform HiPS service.

2 Overview¶

A HiPS data set is a pre-generated tree of image files or other information from a sky survey. It is structured to support hierarchical exploration of data taken from a survey, often through panning and zooming via an interactive HiPS client such as Aladin. The HiPS naming structure is designed to allow one-time generation of a static, read-only tree of files that provide the HiPS view of a survey. Those files can be served by any static web server without requiring a web service. The client is responsible for providing any desired user interface and for choosing which files to retrieve, done via algorithmically constructing URLs under a base HiPS URL and then requesting the corresponding file from the server.

We do not expect to frequently update the HiPS data sets. Instead, during a data release, we will generate the HiPS data sets for that release, and then serve those data sets for users of that data release.

3 Authentication¶

Most HiPS data collections are public and therefore do not require authentication. However, for Rubin Observatory, the full HiPS data sets for the most recent data release will be available only to data rights holders and will therefore require authentication.

Older data releases are expected to become public over time and thus not require authentication. If that happens, we will serve those HiPS data sets directly from Google Cloud Storage as a public static web site, rather than using the techniques discussed below. Those public web sites will use separate domains per data release, following the long-term design discussed under URLs.

It’s also possible that Rubin Observatory will want to supply HiPS data down to a certain resolution without authentication, and require authentication for the higher-resolution images. If this becomes a requirement, we will implement this by creating separate HiPS data sets for the public portion and serve it at a separate URL from the HiPS data sets that requires authentication. The HiPS data sets that do not require authentication would be served directly from Google Cloud Storage as described above.

4 URLs¶

For DP0.2, there will be six HiPS data sets: one image data set for each filter band chosen from URGIZY.

These will use the URLs /api/hips/images/band_[urgizy] at the domain of the Science Platform deployment (data.lsst.cloud for DP0.2).

We may, over the course of DP0.2, add a seventh image data set (possibly at /api/hips/images/color_gri).

The /images path component is in anticipation of possibly adding HiPS data sets of non-image survey data (such as catalogs) in the future.

In the future, we will rework the URL structure for the Rubin Science Platform to use separate domains for separate aspects and services provided by the platform. This allows isolation between services by moving them into separate trust domains, and is discussed at length in SQR-051.

Once that work is done, HiPS (like many other services) will move to its own domain.

The long-term approach will require generating a separate authentication cookie specifically for HiPS (see the Google Cloud Storage design), so that domain will not be shared with other services.

The domain will probably be something like hips.api.<domain> or hips-<release>.api.<domain>, where <domain> is the parent domain of that deployment of the Rubin Science Platform (such as data.lsst.cloud) and <release> is an identifier for a data release.

At that time, we will also add a way of distinguishing between HiPS trees for different data releases, either by adding the data release to the domain or as a top-level path element in front of the HiPS path, whichever works best with the layout of the underlying storage and the capabilities of Google CDN.

We will then serve the HiPS data sets for each data release from separate URLs, using a similar configuration for each data set that requires authentication.

This will also make it easier to remove the authentication requirement for the HiPS data set for older releases, when they become public.

The paths to the image HiPS data sets will then be /images/band_[urgizy], dropping /api/hips from the paths discussed above.

5 HiPS list and registration¶

The HIPS standard has a somewhat confused concept of a “HIPS server,” which publishes one or more HiPS surveys. Each HiPS server is supposed to publish a HiPS list, which provides metadata for all of the surveys published by that server. It’s unclear how this is intended to interact with authentication, since HiPS surveys are normally public.

There are two ways we can interpret this.

One is to treat each published HiPS data set as a separate “HiPS server.”

The HiPS properties file at the root of that data set (at /api/hips/images/band_u for DP0.2, or /images/band_u in the long-term approach) would then double as the HiPS list for that “server.”

In this scheme, the HiPS list would be protected by the same authentication as the rest of the HiPS data set.

Each HiPS data set would then be registered separately in the IVOA registry.

Public HiPS data sets could be registered with public HiPS browsing services, but each would have to be registered separately.

A better approach would be to publish a HiPS list for all published HiPS data sets at a separate URL. There are two possible levels of granularity: one HiPS list for all HiPS data sets in a given data release, or one HiPS list of all HiPS data sets from all data releases produced by Rubin Observatory. We may wish to publish both, or even several versions of the all-release HiPS list (one for public data sets and one for all data sets including those requiring authentication, for example).

For example, for a hips-<release>.api.data.lsst.cloud collection of HiPS data sets, we would publish the HiPS list at https://hips-<release>.api.data.lsst.cloud/list.

This would be world-readable and would be registered in the IVOA registry for that deployment.

The HiPS data sets that require authentication would be marked as private.

Alternately, or additionally, we could publish a cross-data-release HiPS list at an address like https://api.data.lsst.cloud/hips/list, and register that in the IVOA registry.

That single HiPS list could then be registered with public HiPS browsing services, assuming they correctly understood that the private HiPS data sets would not be browsable without separate authentication.

For DP0.2, we will not not publish HiPS lists beyond the root-level properties file for each HiPS data set, and will not have an IVOA registry.

We will revisit this approach once we’ve implemented the change to Science Platform URLs discussed in URLs.

6 Storage¶

HiPS data sets will be stored in Google Cloud Storage buckets. The object names in the bucket will match the URL paths discussed in URLs, and the bucket will contain only HiPS data sets and associated metadata. When we generate a new group of HiPS data sets, such as for a new data release, we will create a new Google Cloud Storage bucket to hold those new data sets.

This decision assumes that the HiPS data will be small enough or the price of Google Cloud Storage will be sufficiently low that it’s reasonable to store the HiPS data there.

6.1 Options considered¶

There are two main options for where to store HiPS data.

6.1.1 POSIX file system¶

The most commonly-used tools to generate a HiPS data set assume they will be run in a POSIX file system. One option would therefore be to leave the HiPS data sets in the file system where they were generated and serve them from there. This would make it easier to serve the HiPS data sets using a static file web server (see Web service). It is the natural storage anticipated by the HiPS standard.

However, using a POSIX file system would lock us into running our own service to serve the data, since there is no standard Google service to serve data from a POSIX file store. In general, POSIX file systems are second-class citizens in a cloud computing environment, and object stores are preferred and have better service support. In Google Cloud in particular, it’s harder to manage multiple POSIX file stores than it is to manage multiple Google Cloud Storage buckets. While we will need a POSIX file system to provide home directory space for interactive users, we would prefer to minimize our use beyond that. For example, we expect the primary repository for each data release to be an object store.

6.1.2 Google Cloud Storage¶

As mentioned above, this is our preferred repository for project data that is stored in the cloud (and HiPS data is sufficiently small that cloud storage for it should be reasonable). Google also supports serving data directly out of Google Cloud Storage, which should allow us to eliminate our web service in the future, instead serving data directly from the GCS bucket, augmented with a small bit of code to check user authentication and create directory listings. (See Web service for more details.)

This also allows us to easily create new GCS buckets for each release of HiPS data sets, manage the lifecycle of test or invalid versions of HiPS data sets by deleting the entire bucket, and choose appropriate storage (for both cost and redundancy) to fit the requirements of HiPS data, rather than the more stringent requirements for interactive POSIX file systems.

The drawback of this approach is that we must either use Google’s ability to serve data directly from Google Cloud Storage, or we have to write a web application to serve the data.

7 Web service¶

For the immediate requirement of a HiPS service for the DP0.2 data preview release, we will use a small FastAPI web service that retrieves data from the Google Cloud Storage bucket. In the longer term, we will switch to serving the HiPS data sets directly from Google Cloud Storage buckets, using helper code (probably via Cloud Run) to set up authentication credentials.

For DP0.2, we will not provide directory listings of available files at each level of the HiPS tree, and instead rely on client construction of correct file names (as enabled by the HiPS standard). This will be added in post-DP0.2 development, most likely as part of moving to serving files directly from Google Cloud Storage buckets.

7.1 Options considered¶

There are three major technologies that could be used to serve the HiPS data, and a few options within those that we considered.

7.1.1 NGINX¶

The HiPS standard is designed for serving the data set using an ordinary static file web server.

NGINX is already used by the Rubin Science Platform, and using NGINX to serve the data has the substantial advantage that static file web servers are very good at quickly serving static files with all the protocol trappings that web browsers expect.

For example, they will automatically provide Last-Modified and ETag headers, handle If-None-Match cache validation requests correctly, and use the operating system buffer cache to speed up file service.

NGINX can also automatically create directory listing pages for easier human exploration of a HiPS data set.

However, in the Rubin Science Platform environment, there are several serious drawbacks.

The Science Platform is Kubernetes-native and does not use a traditional web server configured to serve from a POSIX file system at any other point, nor is it expected to in the future. Using a web server such as NGINX still requires running it as a separate deployment specific for HiPS. This is also not a common configuration for NGINX in a Kubernetes environment (as opposed to using NGINX as an ingress web server, which we already do, but which does not serve static files). It would require finding an appropriate container, configuring it for our purposes, and keeping it up to date with new NGINX releases, since NGINX is an active target of attacks).

Using this approach also requires the files live in a POSIX file system that’s mounted into the NGINX pod. As discussed in Storage, we would prefer to use Google Cloud Storage as the default storage mechanism for project data. That also means this is not a stepping stone towards serving the data directly from Google Cloud Storage, which is the best long-term solution (as discussed below).

Finally, this approach requires writing and maintaining NGINX configuration, which introduces a new pseudo programming language.

7.1.2 Google Cloud Storage¶

The best service is one that we don’t have to write or maintain and can instead enable with simple configuration. Here, that’s serving the data directly out of Google Cloud Storage. If, like other astronomy sky surveys, our HiPS data set was public, this would be the obvious approach. Google Cloud Storage is extremely good (and fast) at static file web service from a GCS bucket and supports all the caching and protocol details we could desire.

Directory listings are not a native feature of Google Cloud Storage, but can be provided easily for browsers supporting JavaScript by using gcs-bucket-listing. (We will have to test the performance of this approach with our HiPS GCS bucket to ensure that it scales to the huge number of files that will be part of a collection of HiPS data sets.)

Unfortunately, our HiPS data set requires authentication, which means that Google Cloud Storage is not suitable out of the box.

Our authentication is done with bearer tokens specific to each Rubin Science Platform deployment (see DMTN-193). This is normally handled by the ingress for that Science Platform deployment, which sits in front of all Science Platform services and can uniformly apply the security and access policy. Serving data directly from Google Cloud Storage would be done from the Kubernetes cluster and thus would not go through the ingress, and would therefore have to us a separate mechanism to set appropriate authentication credentials after login and to check those authentication credentials.

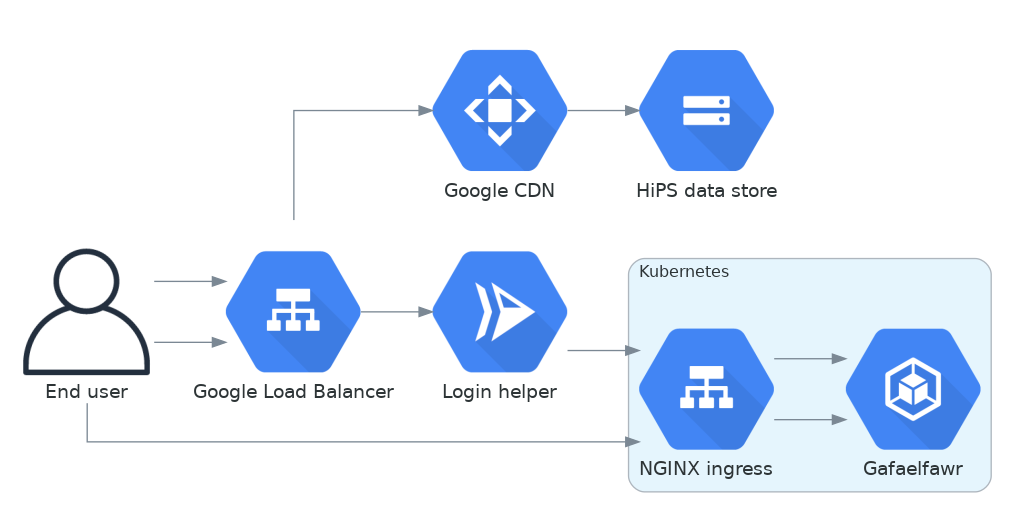

Google does provide a mechanism to support this by combining Cloud Load Balancing, Cloud CDN, and Cloud Run. Here is what that architecture would look like in diagram form.

Figure 1 Google Cloud Storage architecture¶

If the user were not authenticated, the load balancer would route the user to a URL backed by the login helper Cloud Run function. It in turn would redirect the user to Gafaelfawr in the appropriate cluster for authentication. On return from that redirect, it would set a signed cookie for the CDN. The load balancer would recognize that cookie and pass subsequent requests through to the CDN, which would verify the cookie and then serve files directly from Google Cloud Storage.

We’ve not used this approach for the Science Platform before, and this login approach would benefit considerably from the multi-domain authentication approach proposed in SQR-051 but not yet implemented. It’s therefore not the most expedient choice to get a HiPS service up and running for DP0.2 and public testing.

This appears to be the best long-term approach, with the best security model and the smallest amount of ongoing code or service maintenance, but will require more work to implement.

7.1.3 Web service¶

Writing a small web service to serve data from Google Cloud Storage is the simplest approach, since we have a well-tested development path for small web services and such a service can use the authentication and access control facilities provided by the Kubernetes ingress. This is the approach that we decided to take for the short-term DP0.2 requirement.

There are a few drawbacks to this approach. The first is performance: rather than serving the data through the highly-optimized and highly-efficient Google frontend, or even the less-optimized but still efficient NGINX static file service, every request will have to go through a Python layer. However, the additional delay will likely not be significant for early testing.

The second drawback is the complexity that has to be implemented manually in Python. Static file web servers do a lot of protocol work that has to be reproduced manually: providing metadata for caching, responding to cache validation requests, mapping files to proper MIME media types, sanitizing path names to protect against security exploits, generating directory listings, and scaling. This required several days of implementation work, without implementing directory listings, and potentially will require more debugging and maintenance going forward. This is part of the reason for preferring use of Google Cloud Storage directly in the longer term.

As discussed in Storage, the data could be served from either a Google Cloud Storage bucket or a POSIX file system. The POSIX file system approach would be simpler since it would permit use of standard static file server modules in Python web frameworks. However, for the reasons stated there, we chose Google Cloud Storage as the storage backend.

Given that, there are two ways to serve the files:

Stream the file from Google Cloud Storage through the web service to the client. This adds more latency, load, and network traffic because the file in essence has to cross the network twice: once from GCS to the Kubernetes cluster and then again to the client. It also requires Python code sit in the middle of the network transaction and pass the bytes down to the client.

Redirect the client to a signed URL that allows them to download the file from Google Cloud Storage directly. This is more efficient, since generating the signed URL doesn’t require a Google API call and Google Cloud Storage itself then serves the file. However, it inserts a redirect into the protocol flow, which may confuse some HiPS clients, and it means that the URL a user would see in a web browser is a long, opaque blob with the Google signature attached.

Either approach would work, but since the goal of the initial implementation was expediency for testing, the second option raised more unknown factors, and we expect to replace it with an approach using Google Cloud Storage directly, we chose the first option as the simplest approach.

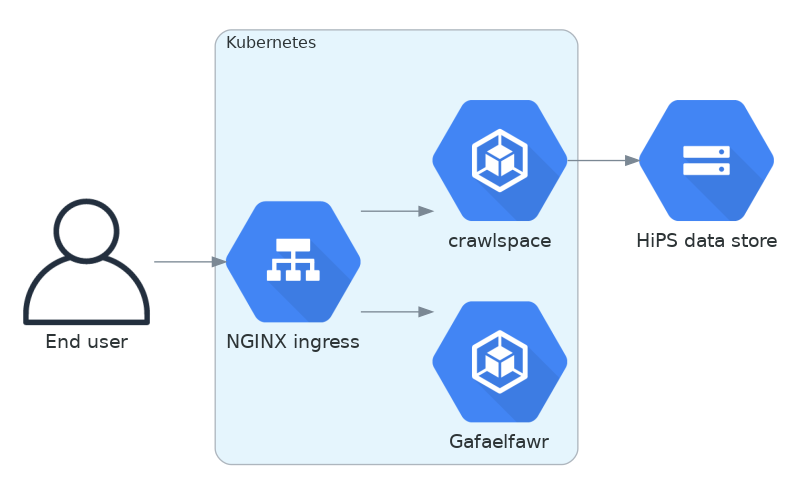

We implemented this approach via a small, generic static file web server backed by Google Cloud Storage called crawlspace.

Here is what this architecture looks like in diagram form.

Figure 2 Web service architecture¶

crawlspace tells clients (via the Cache-Control header) that all files can be cached for up to an hour.

This is relatively short for testing purposes.

We will likely increase that for the eventual DP0.2 service, since we expect HiPS files to be static once generated.

crawlspace attempts to support browser caching by passing through the Last-Modified and ETag headers from the underlying Google Cloud Storage blob metadata, and implementing support for If-None-Match to validate the cache after the object lifetime has expired.

8 Top-level web page¶

It’s conventional to provide an HTML page at the top level of a HiPS data set that summarizes, in a human-friendly way, information about that HiPS data set. For HiPS image data sets, often that HTML page also embeds a JavaScript HiPS image browser such as Aladin Lite.

For the initial DP0.2 release, we will not generate a top-level index.html page.

The expected initial use of HiPS is as context images for catalog and FITS image queries in the Science Platform Portal, rather than direct use via a HiPS browser.

We expect to revisit this in future development, possibly by linking to or embedding the Science Platform Portal configured to browse the HiPS data set.

9 References¶

- crawlspace

The crawlspace static file web service backed by Google Cloud Storage.

- DMTN-193

General overview and discussion of web security concerns for the Rubin Science Platform.

- IVOA HIPS 1.0

The current standard for the HiPS protocol, dated May 19th, 2017.

- Securing static GCS web site

Google tutorial on how to secure a static web site using Cloud Run to manage the login flow.

- SQR-051

Proposed design for improving web security of the Rubin Science Platform. Relevant to this document, it advocates for using separate domains for separate aspects or services of the Science Platform for better trust isolation.